While I was on traveling over Thanksgiving, I read The Son by Phillip Meyer, which is a literary western, in the tradition of Larry McMurtry. Indeed it is kind of a fusing of McMurtry’s historical and contemporary novels, with three parallel storylines, one beginning in the 1840s, one in 1917, and one stretching from WWII to today.

While I was on traveling over Thanksgiving, I read The Son by Phillip Meyer, which is a literary western, in the tradition of Larry McMurtry. Indeed it is kind of a fusing of McMurtry’s historical and contemporary novels, with three parallel storylines, one beginning in the 1840s, one in 1917, and one stretching from WWII to today.

The Son has a particularly bleak worldview. A few types of people make an appearance: those forged of iron, who take and know they take, who know that there is no fairness in the world. They are not good but they are the best of a bad lot. There as those who take, but pretend they have some moral right to the things they take. These are hypocrites, but perhaps not particularly interesting as they do not make up any of the major roles in the book. Then there are the weak, with moral qualms, who will not take, and so are stolen from again and again. There are no nurturers, no care-givers.

The 1800s storyline follows Eli, the family’s progenitor, who is captured by Comanche, then goes on to fight in the Confederate army, and found a cattle operation and later an oil business. The early 1900s storyline follows his son, who is tortured by the way his family takes and takes, and his inability to accept it is his downfall. The modern storyline follows his grand-daughter, a woman who has nothing in common with other women. She wants to have the strengths and successes of a Texas man, but her sex denies her that.

This is an ecological Western, as perhaps, they all are: concerned with a dying way of life that was dying even as it was born. The frontier can only be conquered once, and then it is settled, and the qualities in men that made them capable of the cruelty necessary to settle it are no longer the skills needed. Those who survive must change to steal and pillage in new ways.

A scene from this novel that stayed with me is when an Easterner interviews the returned captive of the Comanche with a narrative already in his mind: that the savages are noble in some way. To which our hero responds that they may be, but where was this concern for the nobility and perfection of the native when the Easterner’s grandparents were killing off their natives? It’s an unanswerable question. What is the use in feeling badly about the deaths that bought today’s prosperity?

Is there any kind of wealth that is not bought from death and injustice? The Son answers no. This is a Western for the new millennium, tracing the death of the Texas ecology, through overgrazing and then the depredations of oil, and what is the future after that? Does the world go the way of frontier Texas?

And yet, this is a deeply conservative book, in the way of conservative, strict-father morality. The only kind of communal society that works the Comanche, and it is rapacious, like nature, red in tooth and claw, but controlled by the challenges of survival. Other tribes and band that act as a check on any tribe that becomes too big and rich. There is no room for liberal, nurturing government, for fairness, for caring for the weak simply because they are weak. The Comanche practice a harsh communism, where loyalty to the collective is so strong that in lean times, blind children are killed, so they will not eat food that could go to more useful members of the tribe. They exist in a state of pure nature, as, I suppose do the Texas oilmen, obeying their nature to become as fat and wealthy as possible, no matter the cost to anyone else.

This book left me with the feeling that nature will balance out us humans soon enough and with as much blood and violence as ever we visited on others. For millenia, humans lived in places, in a balance with nature, but in 100 years, Texas became a desert, and we took oil out of the earth. The Comanche dropped seeds when they traveled, which grew up into the trees that made the straight shoots they cut into arrows. We don’t do this anymore. We borrow from the future instead of seeding for it.

I gave this book five stars on Goodreads, even though it wore its philosophy on its sleeve, and all the characters were given to internal monologues about the difficulty of their lives–or perhaps because of it. I can respect a book with such a relentless, and to me, seductive worldview. The worldview of this book is not mine, but I am attracted to it, and while I was reading the book, I could not reject it, as I could with, say Gone Girl, whose worldview is so alien to me that I could only enter into it occasionally. I couldn’t stop thinking about The Son, for a long time after I finished reading it. Its view of humanity, and its implications for our future are too frightening and close to my own nightmares, to be easily forgotten.

I used to keep another blog where I made random updates on my life and whatever I was thinking. Self-indulgent, yes, but it gave me a place to muse about things. I miss that.

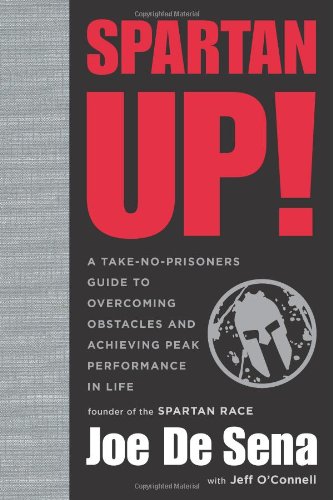

I used to keep another blog where I made random updates on my life and whatever I was thinking. Self-indulgent, yes, but it gave me a place to muse about things. I miss that. Before I went on vacation I read two very different books about athletic achievement. One was What I Talk About When I Talk About Running by Haruki Murakami, and the other was Spartan Up! by Joe De Sena. Murakami is a fiction writer I greatly enjoy. De Sena is an investment banker who retired from that and started Spartan Races, a type of obstacle racing.

Before I went on vacation I read two very different books about athletic achievement. One was What I Talk About When I Talk About Running by Haruki Murakami, and the other was Spartan Up! by Joe De Sena. Murakami is a fiction writer I greatly enjoy. De Sena is an investment banker who retired from that and started Spartan Races, a type of obstacle racing. Yes, you can always make the choice to run the ultra marathon, take the 24 hour bike ride, but you, Joe De Sena, have a wife who can take care of your 4 children while you exhaust yourself. Sometimes the hard work is not pushing yourself to your physical limits, but doing the day to day tasks. Okay, that got a little personal, but I couldn’t help but think that his wife is doing a lot of unsung work.

Yes, you can always make the choice to run the ultra marathon, take the 24 hour bike ride, but you, Joe De Sena, have a wife who can take care of your 4 children while you exhaust yourself. Sometimes the hard work is not pushing yourself to your physical limits, but doing the day to day tasks. Okay, that got a little personal, but I couldn’t help but think that his wife is doing a lot of unsung work.

One of the fun things about teaching has been sharing with students a wide variety of writing. My interests often tend toward the fantastical, the weird, the violent, the darkly humorous, and happily, several of my students shared my interests.

One of the fun things about teaching has been sharing with students a wide variety of writing. My interests often tend toward the fantastical, the weird, the violent, the darkly humorous, and happily, several of my students shared my interests.